Guerrero finds path after brain injury

In-game collision halted superb start to GCU goalie's career 1 year ago

Paul Coro

9/23/2022

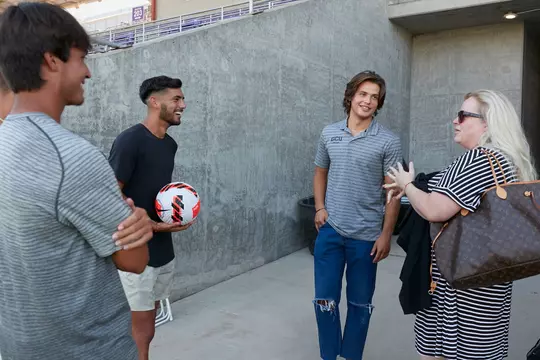

Emerging from the stadium tunnel’s shady shelter, Rafael Guerrero stepped into the sunshine that lit the emerald-green grass where he gleamed a year ago.

The walk, like Guerrero’s past year, went from dark spots to a brighter destination. On this day, the former Grand Canyon soccer goalkeeper took his first steps toward the GCU Stadium south goal since his life flipped in a fearless instant there.

Guerrero stood stoically between the goalposts, where his dreams were coming true last year as a flourishing freshman on a top-25 team. Playing soccer, the flame that lit his world for most of his first 20 years, is more of a wistful memory now.

But he is fortunate to stand and fortunate to have the memory.

In that 18-yard box a year ago this weekend, Guerrero laid limply on the grass – unconscious – with his forehead gashed open to the skull after his hard-charging, game-winning save came with a violent collision 40 seconds before a final horn would have sounded.

“I thought he was dead,” said his mother, Bianca Burns-Guerrero, who was watching from the grandstand.

Rafa spent 23 minutes on the field in front of 2,017 silent spectators. Three days in intensive care with the worst sports head injury the doctors had ever seen. Three weeks of neurological rehabilitation. Six months of occupational, physical and cognitive outpatient therapy. A lifetime of healing from what he lost and praising what he did not after a remarkable recovery.

Jose Pablo Rafael Guerrero – “Rafa” – knows it is a blessing to feel, think and move normally now, but it is also his curse because only images of unimproved, permanent brain damage show why playing any contact sport again could be catastrophic.

“I just remembering thinking, ‘I am going to go out 100%, no fear,’ ” Rafa said of his best game’s final play. “And then that’s all I remember. I was preparing for the whistle to blow. But in the 90th minute, anything can happen … clearly.”

But in the 90th minute, anything can happen … clearly.Rafael Guerrero

Rafa, a native of Tucson, Arizona, was 3 when he started playing goalkeeper because he was the tallest boy on the team. His passion and potential sent him to three developmental academies before signing with GCU in 2021, when his joy for the game rapidly restored.

Feeling supported and valued, Rafa thrived and became the starting goalkeeper by the Lopes' second match of the season at age 19.

His athletic instincts were dazzling as he batted, dived and kicked his way to the 12th-best save percentage (.857) in the nation.

Bianca, a single mother of three, did not recognize this more expressive version of Rafa, who was flashing smiles and hugging teammates after winning his first collegiate start.

“I don’t recognize me either,” Rafa told her.

Before the Sept. 25 conference opener against Seattle U, Rafa was recording a day-in-the-life video for his Tucson youth soccer club to share his excitement and enjoyment about being a Lope.

That night, No. 99's performance was carrying GCU to a 1-0 win with a midair, backward-diving save and a left-footed kick save in a one-minute span. Fans barely caught their breath from his sixth and seventh saves before the eighth save made them hold it.

In the match’s final minute, a pass led Seattle U midfielder Levonte Johnson too far. Fifteen yards away from Johnson, Rafa left the goal area to charge the ball in between them as Johnson tried to catch up to the bounding ball.

Rafa dived forward with his hands outreached to smother the ball, effectively deflecting the ball away as Johnson extended his right leg in an attempt to tie the game. Johnson’s momentum continued into Rafa, who was knocked to his back with legs and hands crossed.

“The doctors told me that the chances of me being struck by lightning were higher than the chance of a knee hitting that particular area of my brain at the intensity that it did,” Rafa said. “The amount of times that I’ve done that in 20 years of life is probably in the thousands.”

From 5 yards away, GCU teammate Justin Rasmussen ran to Rafa and turned him fully face up to expose a 5-inch gash that later required 37 stitches. Rasmussen and Seattle U’s Rory King turned to the GCU bench with panicked expressions and urgent waves for medical help.

“You could see tears on Esai (Easley) and Justin,” Lopes defender Rodolfo Prado said. “We were in shock. The Seattle guys were in shock.”

Rafa remained unconscious for at least 10 minutes while he was placed in a cervical collar. Dr. Kareem Shaarawy, GCU’s head team physician, was on scene and assessed that his respiratory patterns were normal. But he also saw the deep laceration on the left side of his skull, giving him concern for potential severe head injury, internal bleeding, respiratory depression and paralysis.

In the tense stands, a pair of GCU students approached Bianca in her seat, where she sat each game and continued their tradition of signaling 1-4-3 to each other for “I love you.”

“These girls prayed, ‘Thank you for his healing. Look after him and his family,’ ” Bianca said of the strangers. “That is exactly what I needed. If I could ever find those girls, I would thank them because they flipped a switch in me to think, ‘He’s going to be OK.’ ”

The ambulance arrived at the north end of GCU Stadium with the fans' first sounds in 12 minutes coming to encourage walking paramedics to move faster across the field to Rafa.

At the same time, Bianca was joined arm and arm by GCU assistant coach Austin Nyquist as they moved through players standing with hands on their mouths and heads or huddling in prayer. Rafa, who awoke on the gurney, was loaded into an ambulance parked in front of his goal and headed 5 miles to St. Joseph’s Hospital, home to the world-renowned Barrow Neurological Institute.

The neurosurgeons and trauma surgeons examining Rafa thought he had been in a car accident from the looks of his skull-exposed wound.

Imaging of his head, neck, chest, abdomen and pelvis reassured Rafa’s health below his head, but there was diffuse bleeding on his brain from an acute subarachnoid hemorrhage. The crash shook, twisted and sheared his brain, damaging each lobe.

Rafa was diagnosed with a diffuse axonal injury, preventing axons from carrying impulse messages to other parts of his body.

“Imagine you’re driving on the freeway and you can’t exit the freeway when you have to get somewhere,” said Shaarawy, who is also a St. Joseph’s sports medicine physician. “Ultimately, you have to find another path. He had a lot of road closures throughout the brain.”

Imagine you’re driving on the freeway and you can’t exit the freeway when you have to get somewhere. Ultimately, you have to find another path. He had a lot of road closures throughout the brain.Dr. Kareem Shaarawy

After Rafa spent three days in the same clothes, Bianca headed to Target to buy a new outfit when the nurse called and said, “There’s somebody who wants to talk to you.”

Rafa woke up during suturing and screamed in pain before his first words: “Will I play?” He does not remember that, or anything that happened for the next week, but there were other pressing concerns.

In addition to his short-term memory, his balance was poor. He would forget a “Where the Wild Things Are” page that he had just read. His vision and speech were limited. He did not know his birthday and could not write his name, tie his shoes, tell time or assemble shape puzzles.

The university allowed his mother, who has a younger son and older daughter in Tucson, and Rafa to live at GCU Hotel for three months while he underwent occupational, physical, speech, cognitive and emotional therapy at Barrow Neurological Institute.

Healing became an 8-to-5 shift for them, as Bianca left her insurance job for three months and went back and forth to Tucson to be there for her adult daughter and a 15-year-old son with Asperger’s Syndrome.

Rafa went from falling down to the left each time he stood without a harness to joining a rock climbing gym and swimming laps. Rafa initially could not hit an airborne balloon with a stick but progressed to feeling and moving like his old self, which fueled false hope that he would play soccer again for a team that went to the program’s third NCAA Division I tournament appearance.

“I just thought I was going to go back to normal life in a week or two,” said Rafa, who emailed GCU teachers for makeup work in expectation of an imminent return. “I didn’t realize how bad my injury was or the state that I was in beforehand. Each day, I started to realize just how affected I was by this injury. The contrast between how I was feeling and how my brain was frustrated me.

“In every hospital room, a wheelchair was the first thing I saw. They really thought that I was not going to be able to walk or talk or do anything that I’m able to do. Every new doctor was almost condescending, not intentionally, with the way they spoke to me because they were perceiving me by only reading my charts and data. By the medical examinations and the data behind my injury, I should not be able to talk or walk or think at the capacity that I am now.”

Outwardly, he kept high spirits as he progressed, and abilities were restored. His short-term memory was the slowest to restore, making him search for a word at times despite being an eloquent, deep thinker. Amid dark times, he said his mother was his “bright light.”

Bianca told Rafa, “I have screamed. I have cried. I have melted down. I don’t see any emotion. Are you going to feel it?”

Internally, Rafa constantly asked “Why me?” but also knew he was blessed to be walking and talking with an unaltered personality.

By March, Rafa no longer needed the occupational and physical therapy, which the 20-year-old underwent alongside senior citizens. He continues his neuropsychological therapy.

“We can’t do anything more for him,” a physical therapist told the Guerreros in April. “He does more than a fully functioning person. He’s smarter than I am.”

Rafa needed an escape for self-exploration of his changing identity. With savings from summer jobs, he created a European itinerary of five weeks in Genoa, Italy, with side trips to northwest Italy and southern France before spending four weeks in Athens and Naxos, Greece.

Rafa continued his straight-A studies online with GCU honoring his scholarships. He may return to campus, but there are too many inquiries and flashbacks for him to face at this time. As a Professional Writing major, Rafa has kept a journal during his trips of personal introspection and cultural inspection with a nod to his idol, late travel documentarian Anthony Bourdain.

After receiving doctors’ August final ruling that he will not be cleared to play any contact sport again, Rafa immediately booked a monthlong escape to Nayarit, Mexico.

To that point, Rafa had put on the face of a realist who dismissed remote chances that he would play soccer again. But, truly, he was driven in his rehabilitation by the slim hope of a return to the point he regularly ate heads of Lion’s Mane mushrooms, which can stimulate brain cell growth.

“It has been similar to the process of grievance,” Rafa said. “When you lose someone close to you, there’s denial all the way through acceptance. The first few months was denial. It was, ‘I’ll be back. The doctors are wrong.’

“I spent almost every second of every day for the past five years, at least, playing soccer. I committed all of my childhood and sacrificed so much of my personal time to soccer. Having to face that soccer is no longer has been angering, saddening and difficult.”

“You can see it in his eyes that he misses it.”GCU teammate Rodolfo Prado

Rafa did everything doctors asked with a resolute fight. He progressed to where he was living life normally in nearly every aspect and filling the void of soccer wins with rock climbs and Sudokus.

But the magnetic resonance imaging on his brain would not allow Rafa to resume a soccer career that had been on a rapid trajectory. Another head trauma could be catastrophic, but that intangible makes acceptance more difficult when Rafa feels and acts so well.

“The picture underneath the brain is what doesn’t allow us to clear him,” Shaarawy said. “Unfortunately, it’s a what-if scenario. If he has another brain injury, you don’t know what the outcome is.

“The hardest part about being a physician is when you can’t do anything. When we have all this technology and tools and can’t make someone better, it is a helpless feeling. You’re thrilled and happy for being where we started with lying on a field unresponsive with a bad injury to being a normal college kid. But the fact that I can’t do anything for him to help him play soccer makes this empty.”

Rafa searches for those new life facets that will cumulatively build joy and eventually fill most of his life's pleasures. But for now, standing on the GCU Stadium pitch still evokes memories that are in transition from what he lost to what was gained.

“You can see it in his eyes that he misses it,” Prado said. “It took a toll on all of us.”

The forehead scar that once looked like baseball glove stitching has healed and left a fine line, just like the one that he walks between the gratefulness of how he has emerged from the trauma and the remorse of so much drama.

Rafa wants to ease the concerns of the GCU community and the soccer world that reached out touchingly in masses. His family also appreciates donations of about $27,000 to a GoFundMe account that was started by a family friend, who increased the goal to $100,000 to address wide-ranging expenses beyond insurance coverage.

There are still discouraging days, but Rafa said the frequency of hopeful days is increasing. For now, just visiting GCU Stadium is an emotionally exhausting effort. He envisions a time when he can enjoy watching soccer again, or “dance with discomfort” as he puts it.

“Whether the saffron notes in a dish are there or not, it doesn’t matter to me,” Rafa said. “It has no meaning. But to a chef, it has meaning and purpose. We have the ability to assign meaning to life. With the absence of what I assigned as meaningful, it was hard to think about what else I could do with it. It was the only thing that fulfilled me. It was what I thought I was going to do for the rest of my life.

“With the trips and learning more about myself and life in general, my hope went from being destroyed about the news to having hope that there is more that I need to discover, and there is going to be meaning to my life. It’s exciting that I have the chance and privilege to find other things.”